What do you get from tracking trends?

You know what the third-quarter review meeting means: a packet will be handed out with bar graphs and, no doubt, trend lines on each of about a zillion “key performance indicators” that show:

- This month vs. last month vs. 12 months ago (maybe year-to-date as well)

- The three months’ performance of the current quarter

- The first three quarters of the year

- This quarter vs. last quarter vs. third quarter a year ago

(Of course, tables are included with red, yellow, and green cells measuring performances and variances from targets, for which you are already preparing your explanations as to why you didn’t achieve them, right?)

Data insanity as a source of waste

Many of you know me as a statistician, yet I’ve been talking about organizational transformation in my last two articles and the need to take improvement to the next level—“built-in” vs. “bolt on.” And I do feel that a key catalyst to accelerate this process is my “data sanity” concept.

In case you aren’t familiar with my definition of data sanity: It’s the everyday use of data in a process-oriented context so as to react appropriately to its inherent variation and achieve improvement and better prediction.

Or put another way: Don’t treat all variation as special cause and take actions that increase complexity.

Most days, doesn’t it feel like you’ve been hired to ride in a car with four flat tires going down the highway at 70 miles per hour with your job being to change the tires? And you’re given only one small caveat: You can’t stop the car under any circumstances. However, you are empowered to lecture the driver on improvement or even give her appropriate audio books for self-study (and hope the car doesn’t have an ejector-seat button).

Mark Graham Brown, for whom I’ve developed a respect because of his excellent writings on balanced scorecards, has said:

- 50 percent of the meetings that executives attend involving data are wasted time

- Middle managers waste one hour a day poring over useless data

- 80 percent of published financial data is waste

- 60 percent of routine published operational data is waste

These meetings also result in subsequent work for you and other people looking for reasons why some key indicators went “up” or “down” or didn’t achieve established targets. But because you are very smart people—that’s the problem—you find them. In process parlance, every deviation from a target is treated as a special cause.

The time-chasing special cause explanations could be spent communicating vision and strategy, and be devoted to improvement as the “learning and growth” arm of the business (learning and growth is one of the categories from the balanced scorecard’s original theory).

But anyway… back to the quarterly review meeting

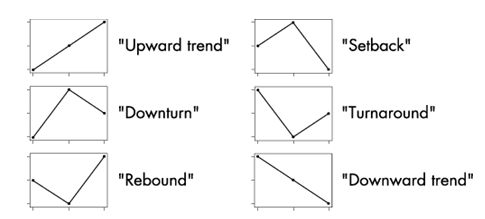

Let’s see, how could three numbers look… and be interpreted?

Isn’t it amazing that given three different numbers, there are six different ways they can manifest? And each one has its “special cause” explanation. But, is it really a special cause?

Also, two of the six patterns fit a widespread preconception of the word—trend: Either all the points go up or all the points go down.

Let’s talk about that ubiquitous word “trend.”

In this case, with three different data points, given the fact that these are two out of six possibilities, there could be a 33-percent potential risk of being wrong by arbitrarily declaring three points a trend, i.e., calling something a trend (special cause) when it is merely a common cause.

Did you know that the statistical rule of thumb (based in theory) to declare a true trend is a cluster of seven data points either all going up or all going down, i.e., six successive increases or decreases? If there are 20 or less points being plotted, one can then use six consecutive points, or five successive increases or decreases.

I give you this rule to mainly tell you what a trend is not, because its occurrence is relatively rare.

What does trend mean anyway?

Putting it in a process context, I like to think of the trend signal as showing a process in transition: You previously had a process that was perfectly designed to get the results it was getting and you have done an intervention (tried to create a beneficial special cause). The process is transitioning to what it is perfectly designed to get given its new inputs (your transition).

And here is the key point: transitioning to what it is perfectly designed to get—at which point it will level off.

Here is a wonderful analogy: The holiday season will soon be here and for many us, it will be time to make our yearly pledge to reduce our weight (sort of like the goal setting organizations do at annual budget time). OK, so we set a target and plan to weigh ourselves every day.

Next, we cut calories (some of us throw in exercise). Throughout the next four weeks or so (especially during the first two weeks), some of us will no doubt see the five or six successive decreases in a row. (Don’t lose heart if you don’t. There is another test to show progress).

In the reading I’ve done, right at the beginning of such an effort, there are about 5 to 10 lb of “water weight” just waiting to be lost if your calorie intake differs significantly from the norm. And if you are able to stay on track, the results in weeks three and four are less dramatic, but still effective: maybe 1 to 1.5 lb a week.

Then what happens? Your body has adjusted to the weight that it is “perfectly designed” to reach given your diet regimen. Any further loss will require another new process (usually more exercise, in my case). And if you haven’t reached your target weight after week four, do not despair. Take your data and put in the trend line. Not only will you be able to tell when you will reach your target weight, you can then project when your weight will go to zero, right?

Of course not, so if this nonsense of doing trend analysis is apparent for your weight, why don’t people make the analogy to organizational processes? This is assuming they have first accepted the fact that they do indeed manage processes.

So, trend = transition.

Here is a more important question: At what value does the trend stop—if there was even a trend in the first place?

Bottom line: Once you account for the number of meeting hours multiplied by salaries, multiplied by benefits, or as in the case of an all-day meeting, an entire day multiplied by everyone’s salary and benefits… how much would data sanity save?